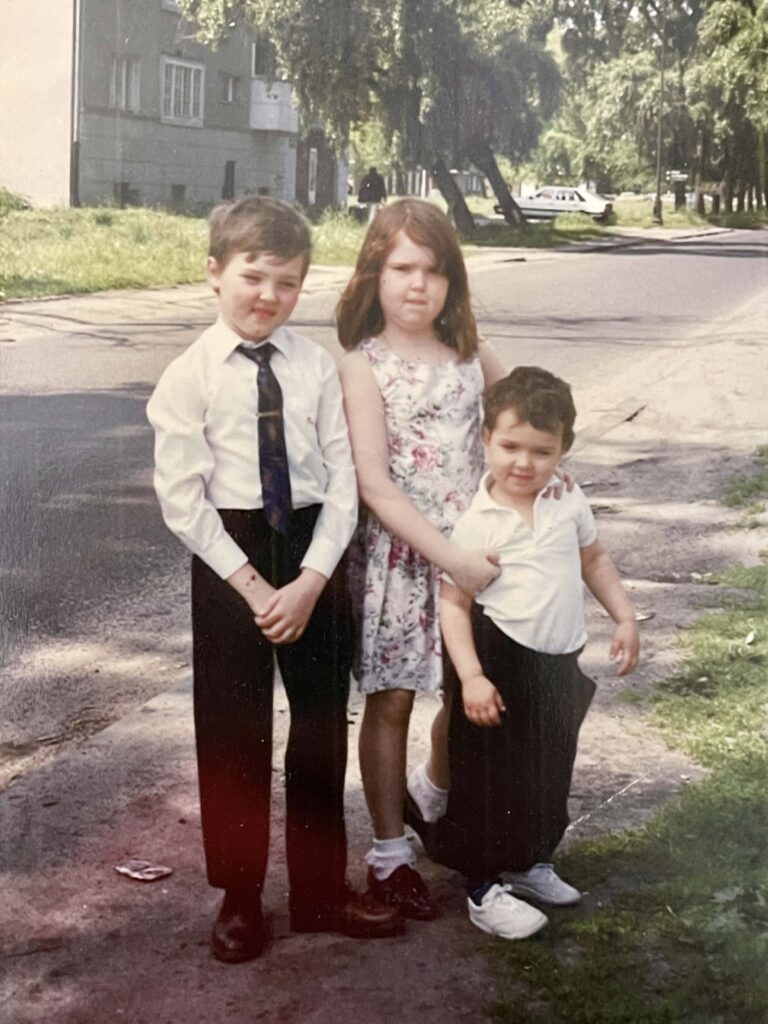

My brother, sister and I outside of our apartment building (and site of the Hoover Institution Library & Archives field office run by my dad, Dr. Maciej Siekierski) on Racławicka Street in Warsaw, Poland, 1992

“Why did you come back to Poland?” This is the question I hear most often when I tell people that I left sunny California.

The answer is complex, and I came to this realization after many years, but in short, “I am Polish and I feel good here in Poland, better than there.”

How did it happen that I was born in Redwood City, on the San Francisco Bay, over 9,000 kilometers from our homeland.

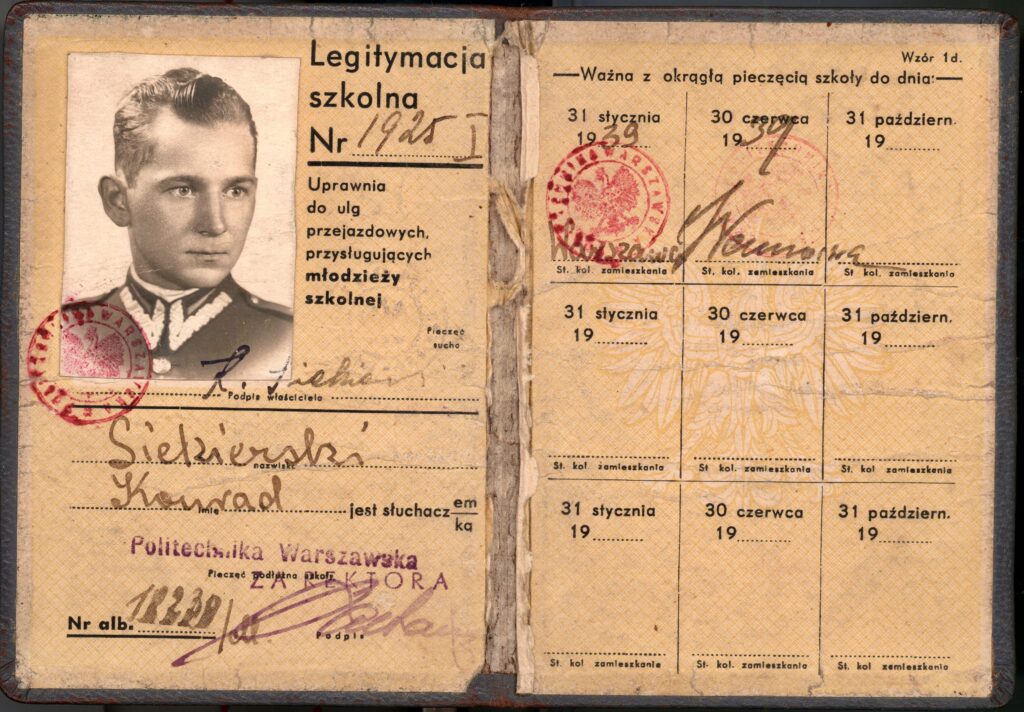

Let’s first go back over 80 years. My grandparents, Konrad Siekierski and Kazimierz Bendisz, officers of the Polish Army, took part in the Defensive War against Germany in September 1939. My grandfather Konrad, who was tasked with organizing the defense of the Vistula bridges in Warsaw, almost lost his life during the German bombing of the capital. Fortunately, the bomb that would have probably killed him by hitting the surface of the Poniatowski Bridge, did not explode.

Konrad Siekierski’s ID card while studying at the Warsaw University of Technology in 1939

After the capitulation of Warsaw, he was imprisoned by the Germans in Oflag VII-A Murnau (a prison camp for officers) in Bavaria. Grandfather Kazimierz, who took part in the fighting in southern Poland, was also sent to the camp in Murnau after his unit’s ammunition ran out. My grandfathers, who knew each other from officers’ school a few years earlier, maintained their friendship until Kazimierz’s death in 2001.

The liberation of the camp by American troops on April 29, 1945 (an important date for me because I was born on April 29, exactly 38 years later) meant a new beginning for Kazimierz and Konrad. However, Poland, “liberated” by the Soviets, was not favorably disposed to pre-war officers, and after years of trying to find their way in the new reality, decisions were made to emigrate to California. Konrad was first in 1962 with his family (including my 13-year-old Dad) and then in 1970, Kazimierz. July 4, 2022 marked the 60th anniversary of their plane landing in San Francisco, a week earlier they had reached New York on the Batory passenger liner.

My dad, two uncles and grandparents aboard the Batory, June 1964

At the age of almost 50, my grandparents were not able to integrate deeply into American society, they never learned English well and their closest circle was family and Polish friends. They were betting on the future, on the generations of their children and grandchildren, that is, on my parents, my siblings and I, uncles, aunts and cousins.

For me, the 1980s and 1990s, spent most often with grandma and grandpa, were a golden era. Countless holidays, birthdays and other family gatherings, and just going to church together. Most often, we went to English-language masses, because the Polish church was too far away to attend regularly.

My first visit to Poland was in 1990 for a month. This gray post-communist reality was in fact a powerful experience for a seven-year-old boy that opened his eyes to a new world. Less than a year later, when my dad, Dr. Maciej Siekierski, curator of Eastern European collections at the Hoover Institution Archives and Library at Stanford University, began a program of collecting historical materials in Poland, especially related to Solidarity, as part of the Institute’s office in Warsaw, which he headed, our entire family moved to Poland for almost two years, from 1991-1993

At that time we lived on Racławicka Street in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, and I attended third and half of fourth grade at the Adam Mickiewicz primary school on Kazimierzowska Street. I remember when I came back from school with tears in my eyes after the first science lesson, “Mom, what’s going on with this spring and winter grain?” I didn’t understand why I had to learn this. The situation later improved after home tutoring by one of my teachers, the late Mr. Bogdanowicz, who tragically died of cancer a few years later in his early 30s.

I remember outdoor education and bisons in the Białowieża Forest, trips to the nearby Iluzjon Cinema and the Palace of Culture. The memories of the time spent with Grandma Helena (my mother’s mother) who stayed in Warsaw after divorcing Grandpa Kazimierz, are priceless. Holy Masses at All Saints Church, the first experience of All Souls’ Day on November 1 and a visit to the Evangelical Cemetery where my great-grandparents are buried, and now my uncle and aunt, veterans of the Home Army, who were still alive at that time. I also remember visiting my dad’s friend who ran a secret printing house hidden behind a false wall in his garage during Martial Law.

Then I also began to understand what poverty was and how much my life in California was different from that in Poland. Among the funnier memories, I remember the first McDonald’s in Poland on the corner of Marszałkowska and Świętokrzyska Streets, where my grandmother ate french fries with a knife and fork, or the first Pizza Hut on Castle Square, where me and my siblings, probably resembling little barbarians to the other guests, were the only ones who ate pizza with our hands.

Visits to Poland took place regularly until I was an adult, sometimes a few years passed between them, but they always happened. Dad’s work involved at least two trips to Poland a year, and at the end of his career even three times.

In California, outside my family home, I learned Polish in Polish Saturday school for several years, organized by the Polish parish then in Mountain View, which now exists with its permanent church as the Polish Mission of St. Brother Albert in San Jose since 1998. Unfortunately, it’s an hour’s drive from our house.

Growing up, even though I was born and raised in California (apart from that 18-month stint in Warsaw), I always felt a bit alienated from my peers. Only as an adult did I realize that the thing is that I am Polish, the phrase “Polish-American” or “American of Polish origin” never suited me, and to this day I correct those who suggest such things by simply saying “that I am Polish.” “

I was raised in Polish culture, by Poles, my three grandparents lived near me for the first 18 years of my life. I was formed in Polish culture, with Polish traditions (especially around Christmas and Easter), and with a passion for Poland’s long and fascinating history (which too often turns into a kind of daunting mathematics with dates, chronology and names to remember, instead of this beautiful and the dramatic saga that it is).

The most important event of my early adulthood related to Poland was a trip here to Kraków as part of the study abroad program of the Kościuszko Foundation in New York. My dad also participated in this program in the 1970s at the same age as me. Times were a bit different then, and as he learned decades later from a file in the Institute of National Remembrance, the security services were surveilling foreign students, but Dad was considered a person with too strongly patriotic or reactionary views and was deemed unsuitable for cooperation.

This program consisted of Polish language, culture, history and literature classes. There were also educational trips and social gatherings. I was in Poland alone for the first time then, without my parents and family. This was another step towards realizing that I could live in Poland. While living in the dormitory, I met many interesting people, one of them is a friend with whom I am still in contact, I was at his wedding 6 years ago. He did not marry a Polish woman, but he is a strongly religious person who appreciates the advantages of living in Poland and is considering the possibility of moving to Poland (he was born in Poland but moved to Canada as a child).

When I finished my bachelor’s degree in history and then master’s degree in library science, I started working full-time as an archivist, also at the Hoover Library & Archives like Dad. He had been working there since 1981 and I officially started working as a student there in 2001, then full-time starting in 2008. Working where the largest archival collections related to the history of Poland in the world outside the country are located, I delved into knowledge about Poland and, also as a curator of exhibitions in the Hoover Institutions museum, I always tried to emphasize the history of Poland and also convey this knowledge to visiting groups, students and educators for whom I prepared presentations.

Giving a talk in Warsaw on the Andrzej Pomian Papers from the Hoover Library & Archives, 2012

The full history of the Hoover Institution’s connections with Poland is a story for another day, but my work there directly inspired my doctoral thesis, which, due to life’s perturbations, was completed a few years later than planned, but was finally defendedin 2022 entitled “The Operations of the American Relief Administration in Poland, 1919-1922”. Without a doubt, it was the greatest period of Polish-American relations in the history of both our nations. I will add that I am a member of the Social Committee for the Reconstruction of the Monument of Gratitude to America, which was located on Herbert Hoover Square on Krakowskie Przedmieście in Warsaw. A sign of thanks for saving millions of Polish, Jewish, Ukrainian and other children and nursing mothers from hunger and poverty in the first difficult years after regaining independence after the First World War. I encourage you to like our Facebook page.

With my dad at the commemorative stone that marks Herbert Hoover Square in Warsaw and where the Monument of Gratitude to America once stood and should rise again, 2010

After years of work at Hoover, however, I felt unsatisfied. The extremely interesting archives could not replace living people, environment and a society that was already flourishing in Poland more than two decades after regaining independence yet again.

In 2012, I decided to ask for a break from unpaid leave from work and went to Poland for 6 months, from August to January 2013. I then took the first steps towards doctoral studies, which I officially started at the end of 2013. I continued volunteering at the Warsaw Uprising Museum, which I had begun doing in 2010, including in the Oral History Archive, where I had the honor to assist with conversations recorded with Warsaw Insurgents and later I conducted several conversations with English pilots on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Uprising, who flew in 1944 to help Fighting Warsaw.

With English airmen who flew to Warsaw’s aid in August 1944, Warsaw, August 2014

I went to my cousin’s wedding, got to know Warsaw street by street, made new friends, and finally proved to myself that I could live alone in Poland, that I could cope, that I was overcoming certain communication barriers and that I could stay here longer. I will add that I also studied Polish for a year at Stanford University just before this period.

At the beginning of December 2013, almost exactly 10 years ago, I made the final decision to connect my future with Poland. It was impossible to work full-time and write a doctoral thesis and only come to Poland for a few weeks, once or twice a year, it was not enough.

I know it wasn’t easy for my dad, especially because we worked together, but he understood. A few years ago, when I was tidying up his office and taking away his personal belongings after he retired, I came across correspondence with one well-known lady, the wife of a former and perhaps future minister, where Dad wrote that “it’s high time for a Siekierski to return to the country. “

I won’t say that every moment and every day of these last ten years was easy and pleasant, but I do not regret this decision. I still face a particular pessimistic attitude that is very different from the mentality of optimism and unlimited possibilities that I learned from America. I think it is changing, especially among younger generations, but I also know that many young Poles have no patience for the pace of change and are considering leaving, I just hope it is not permanent.

Next year I will be renewing my Polish passport, which I received 9 years ago, for the first time. Thanks to the fact that my parents had a civil wedding in Warsaw (and later a church wedding in San Francisco), obtaining citizenship was quite easy. I had to get a copy of my birth certificate from the USA (for this reason I am Nicholas and not Mikołaj) which was then translated into Polish by a sworn translator. After submitting the appropriate documents to several offices, I received an ID card and a passport.

In 2017, I started a freelancing business in which I translate from Polish into English and also provide English tutoring. I have been paying taxes and ZUS for almost seven years, which is what I like least about Poland, but at least I have recently started using our health system, which, apart from the very long waiting time to see an allergy specialist, I cannot complain about. I will say that during these 10 years I have not had a bad experience in government offices, as some people complain about.

I do not deny that my life experiences are very unique, but I think that we can also draw a lot from them regarding the topic of our upcoming discussion on how to encourage our compatriots to return to our country.

Contrary to appearances, I was not closely associated with the American Polish community beyond my childhood, and even then this period did not last more than a few years. My parents were much more involved in the Polish community, especially in the Polish Home in San Francisco in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Currently, I have no contact with Polish organizations in America.

Nobody ever told me that I “had” to return to Poland. I think my choice was even surprising for many people, and of course for Poles who were born and raised in Poland. Many see it as a kind of rejection of a winning lottery ticket.

I am most indebted to my Grandma Helena when it comes to a specific moment in my path back to Poland. Shortly before her death in 2004, she had already lost her eyesight, but she still had great hearing (like I still do). She heard that my Polish was weakening and told me “never lose your mother tongue, never forget Polish.” Since then, I have been trying my best to do so.

My favorite family photo, with all four of our grandparents. Kazimierz and Helena at right and Konrad and Helena at left, Redwood City, 1989

“Why did you come back to Poland?”

Because I feel at home, I feel better among my own people, connected by a common culture, history and traditions. There are, of course, serious political disputes, but from my perspective they are much milder than the ethnic, religious and ideological disputes in the USA. For various reasons, my ancestors left the country, but now it is better here than there, in the West, which many people still think we should catch up to.

I always encourage you to think about what we have here that you couldn’t buy for any money. For example, the sense of security in large Polish cities and the quite universal pride and admiration for our achievements and the history of difficult struggles over the last two centuries.

Everyone likes a good story, especially one in which we play a role. It was when I returned to Poland that I saw an opportunity that did not exist in the United States.

One of my most valuable family souvenirs are buttons from Grandpa Kazimierz’s officer’s uniform, with an eagle wearing a crown. They can be seen in his photo with his prison number in Murnau from October 1939.

Kazimierz Bendisz with his prisoner number in Murnau, Bavaria, October 1939

Tens of thousands of the same buttons lie underground in Katyn, Smolensk, Kharkov and Miednoje, also in Kurapaty near Minsk and Bykovnia near Kiev. When I hold these buttons in my hand, I feel that they weigh more than they should. They carry with them the burden of a certain obligation and responsibility. These thousands of brothers in arms of my grandfathers had their lives brutally interrupted and they were not allowed to raise their children and grandchildren in a free country, which they had painstakingly built for 20 years before the outbreak of the war.

I came back to help write a new chapter of our common history. A chapter that will worthily pay tribute to our grandparents and compatriots who wanted Poland to live in our hearts. They kept this priceless love alive until at last we could return to it and act in our country without fear of repression. To build a homeland that our ancestors, we and our descendants can be proud of.