Late in the evening of August 12, 1919, Herbert Hoover’s train from Switzerland arrived in Warsaw. As Hoover recalled, “In order to be as impressive as possible I was accompanied by several generals and admirals.” He was greeted by the highest representatives of Poland, Prime Minister Ignacy Paderewski, Chief of State Józef Piłsudski, ministers, officials, officers, foreign dignitaries and military bands continuously playing the Polish and American national anthems.

The mayor of Warsaw presented Hoover with bread and salt in a traditional welcome: a huge, round loaf topped with a large salt crystal on a heavy, carved wooden platter. While holding his hat in his right hand, Hoover received the platter with his left, and his wrist quickly began to wobble from the weight. He managed to pass it on to the admiral, who passed it on to the general, watching it “go all down the line to the last doughboy. The Poles applauded this maneuver as a characteristic and appropriate American ceremony.” It would only be the first in many such acts of Polish hospitality.

Herbert Hoover at an open-air Mass on Saski Square in Warsaw, next to him is Papal Nuncio Achille Ratti (later Pope Pius XI), August 13, 1919 (Hoover Institution Archives)

A reception fit for a hero was certainly warranted. For nearly eight months prior to the visit the American Relief Administration (ARA), directed by Hoover, had been shipping hundreds of thousands of tons of food into Poland to be distributed through a network of thousands of kitchens and charitable institutions run by Polish volunteers and overseen by several dozen Americans. The ravages of hunger resulting from the devastation and plunder of the First World War touched millions of Poles, many of them vulnerable children, especially in the eastern borderlands. Thanks to this American intervention, millions were spared from hunger and the effects of malnutrition and thousands from actual starvation. The Americans believed the food was indispensable to strengthen the Poles against the specter of revolution from the east and preserve their freedom.

As Helena Paderewska, the prime minister’s wife, wrote in her memoirs: “He and the devoted young men who worked for him have done more in one year to make the name of America loved and understood than diplomats and wars could do in a century.” She also called him a “miracle maker”. The relief program was not limited to Poland, but encompassed the Baltics, Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, the Balkans, parts of Turkey and even famine-ravaged Russia starting in 1921. Hoover’s superb capacity for leadership and administration, first manifested internationally as head of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, then US Food Administrator and Director General of Relief after the war, earned him a devoted following of friends and supporters that would eventually help to propel him to the presidency of the United States.

Herbert Hoover, Ignacy Paderewski and Helena Paderewska in her Polish White Cross uniform, Warsaw, August 13, 1919

Acting as President Woodrow Wilson’s personal representative, a whirlwind week followed Hoover’s arrival with travel from city to city, meetings with delegations, banquets and ceremonies. As Hoover later wrote, one of the most important stops was a speech at the Wawel Castle in Kraków, near the tomb of Tadeusz Kościuszko, who was not only a Polish national hero but a hero of the American Revolution. Hoover was to speak first, then be followed by a translation by Paderewski. Hoover’s speech only lasted ten minutes since just a fraction of the 30,000 people attending could understand English. Once forty-five minutes had passed into Paderewski’s “translation”, Hoover turned to his Polish aide and asked what he was saying. He responded: “Oh, he is making a real speech.”

Though Hoover was a man of few words, even shy at times, and no world-class orator like Paderewski, he could shine at the appropriate moment. A dinner in his honor in the apartments of the Royal Palace in Warsaw attended by the elite of Polish society, featured only two speeches, Paderewski’s greeting and Hoover’s reply. As Helena Paderewska remembered it, “The latter made a very deep impression, especially on the Americans who were there, many of whom had never met him before. As one of them said later, it was so different from what they had expected, for in it Hoover had shown a strain of poetry, of real fancy, a gift of real eloquence, which was most unusual.” Though no record of the speech exists, it almost certainly touched on the life-saving work being done by the ARA and the critical relationship between nourishing the youngest generation and defending Poland’s hard-won independence that was then only nine months old. He would not have failed to mention the new bonds of friendship and respect being woven between Americans and Poles.

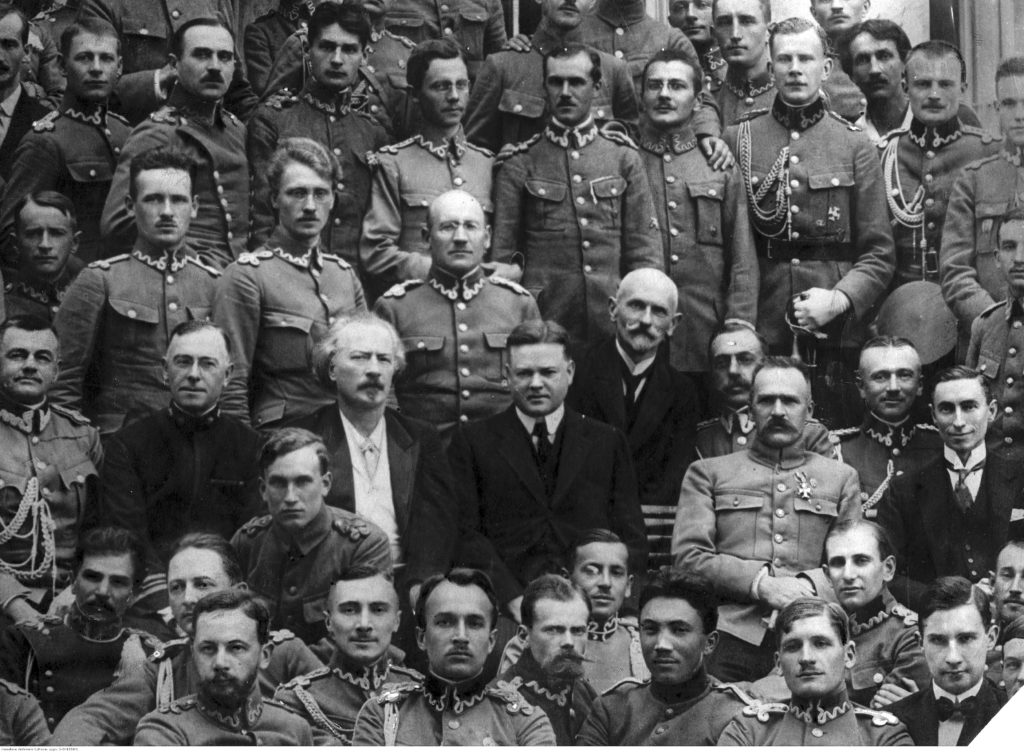

Herbert Hoover, Ignacy Paderewski, Józef Piłsudski and Hugh Gibson, among others, in front of Belvedere Palace in Warsaw, August 13, 1919

Though the lion’s share of the relief program for Poland consisted of credits for the bulk purchase of food that was sold on the open market, the special need for children’s relief was readily apparent and a separate, charitable program was established; with food to be distributed without regard for nationality, class or religion. For this reason grateful children figured prominently in Hoover’s visit. As the first US Minister to Poland, Hugh Gibson, humorously recalled in a letter to his mother: “There were motor lorries filled with children outside and the staircases [in the Hotel Bristol] were lined with more midgets who strew flowers in Hoover’s path. They might just as well have been strewing banana peels for he nearly broke his neck two or three times. It sounds poetic but when I have to go up or down marble staircases without a handrail to hold onto, I am ready to omit the flowers.” This was only to be a prelude to the main display of thanks and affection for Hoover and the Americans.

On the afternoon of August 14, Hoover and his party were taken to the Warsaw Horse Racing Track at the Mokotów Field. As many as fifty-thousand children gathered from all over Poland in a grand parade of gratitude, lasting from the early afternoon into the evening. The scene unfolded before Hugh Gibson’s eyes:

The field before the grandstand was packed with people, mostly small children and the cheers they let out almost took the roof off. The place was filled with bands, all playing, and the march past began at once. The youngsters varied from eight to twelve years, and most of them marched like veterans, and the way they yelled at the sight of Hoover was something worth coming this far to see. A steady stream poured by for two solid hours and the poor man was pretty red-eyed most of the time… An average of once a minute a youngster or group of youngsters was brought up to hand Hoover a bouquet or set a piece of flowers until the tribune all around him was banked high with them… I think most people there grasped the significance of the occasion. If it had not been for what Hoover had done there would have been mighty few of those children alive. Even the youngsters themselves seemed to realize it. Almost any field marshal can go and review that many troops whenever he feels like it, but it doesn’t mean anything in particular and no matter what he had accomplished in the way of military successes I don’t believe the soldier could get the same satisfaction.

Gibson was not the only one to share this sentiment, before departing, the head of the French Military Mission to Poland, General Paul Prosper Henrys, with tears running down his cheeks, turned to Hoover and said, “There has never been a review of honor in all history which I would prefer for myself to that which has been given you today.” Obviously moved by this amazing experience, particularly the site of thousands of barefooted children, within several months, in time for the Polish winter, nearly half a million pairs of shoes, warm stockings and overcoats were on their way to Poland in ARA ships.

Children from Primary School No. 11 in Warsaw holding Polish and American flags in honor of Herbert Hoover, August 14, 1919

While Hoover was the public face of American benevolence, he was not the only one worthy of praise. An entire cast of able men (not to mention women such as the Polish-American volunteer Grey Samaritans) played a critical role in the relief enterprise. Certainly worthy of recognition and praise in their own right but mentioned in brief here: Colonel William R. Grove, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient and Head of the American Mission to Poland in its first phase; Lieutenant Maurice Pate, veteran of the Commission for Relief in Belgium and outstanding leader of the children’s relief program in Poland; William Parmer Fuller, head of the ARA in Poland in its second phase when relief to children reached its peak of over one million meals per day and during the critical months of the Polish-Soviet War when food stocks were evacuated from eastern warehouses; and Colonel Alvin B. Barber, head of the European Technical Advisers Mission to Poland.

Exactly a year after Hoover’s visit, Polish soldiers defeated the Red Army at the gates of Warsaw in the “Miracle on the Vistula”, coinciding with the feast of the Assumption of Mary. A significant role was played by the American pilots of the Kościuszko Squadron who volunteered to fight against the Bolsheviks, and were especially effective against Semyon Budyonny’s First Cavalry Army or “Konarmiya”. The squadron’s founder, Merian C. Cooper, a man whose astounding story could not possibly be done justice in a few lines, had earlier led ARA operations in Lwów, which he had flown into while it was under siege by Ukrainian forces in 1919. He was later decorated with Poland’s War Order of Virtuti Militari. While it is impossible to measure its impact, the massive volume of food and economic aid provided by America to Poland in the preceding eighteen months surely factored into the victory as well.

Herbert Hoover surrounded by a crowd in Lwów in the glade by the Union of Lublin Mound, August 16, 1919 (Polish National Library)

One-hundred years on, the remembrances of Herbert Hoover and the other heroic Americans in Poland leave much to be desired. The Monument of Gratitude to America erected in 1922 on Herbert C. Hoover Square in Warsaw began to disintegrate and was dismantled in 1930 and was never rebuilt.

A positive recent step was the excellent “From Poland with Love” exhibition created by the History Meeting House in 2018 year which displayed colorful panels about this episode in history in the vicinity of Hoover Square, including a full-scale reproduction of the monument.

The Jan Karski Society, named for the legendary courier of the Polish Underground State who informed the Allies of the ongoing Holocaust during the Second World War and himself received American food as a child, appealed to the President of Poland Andrzej Duda for the monument to be rebuilt. When Hoover Square was redeveloped a decade ago the idea of replacing it was apparently dismissed.

The Społeczny Komitet Odbudowy Pomnika Wdzięczności Ameryce (Social Committee to Rebuild the Monument of Gratitude to America), which was founded in May 2023 (I am the deputy chairman), seeks to rebuild the monument on its original location on Herbert Clark Hoover Square on the Krakowskie Przedmieście in Warsaw. You are sincerely invited to like and follow our page on Facebook and connect with us, thank you for all of your support: Odbudujmy Pomnik Wdzięczności Ameryce

An image of the Monument of Gratitude to America near where it once stood on Herbert C. Hoover Square in Warsaw, 2018

For a nation as steeped in history and its associated commemorations, remembrances, symbols and monuments, the absence of a worthy tribute to our most important ally is a glaring oversight. It is worth remembering this shining chapter in U.S.-Polish relations and recognize it as a touchstone for highlighting the great cooperation between our nations in the past and the breadth of possibilities for the years to come. It is our honor to be the heirs to these events, and always remembering them is a noble use of the freedom both our nations so cherish.

Part of the “From Poland With Love” exhibit at the corner of Hoover Square in Warsaw, 2018

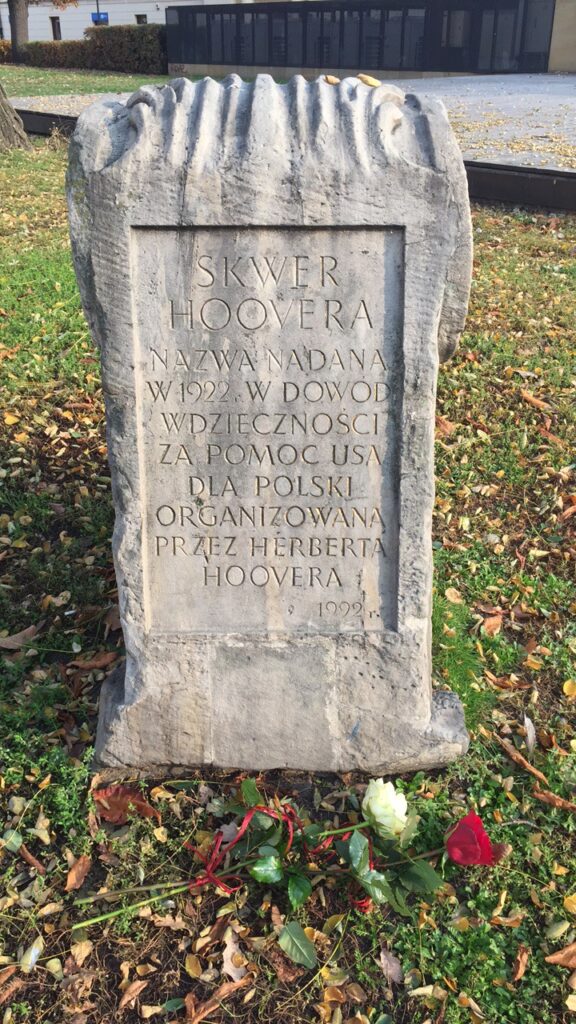

Memorial stone on Hoover Square recognizing American aid to Poland, created out of a fragment of the Royal Castle, placed at the initiative of Dr. Maciej Siekierski in 1992

Further Reading:

An American in Warsaw: Selected Writings of Hugh S. Gibson, US Minister to Poland, 1919-1924 Edited by Vivian Hux Reed (University of Rochester Press, 2018) [Also in Polish]

Helena Paderewska: Memoirs, 1910-1920, Edited by Maciej Siekierski, Foreword by Norman Davies (Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 2015) [Wersja Polska: “Helena Paderewska. Wspomnienia 1910-1920”]

OnFacebook: Odbudujmy Pomnik Wdzięczności Ameryce

One thought on “Herbert Hoover in Warsaw 🇵🇱 Rebuild the Monument of Gratitude to America!🇺🇸”

Comments are closed.