Last week I attended the conference “

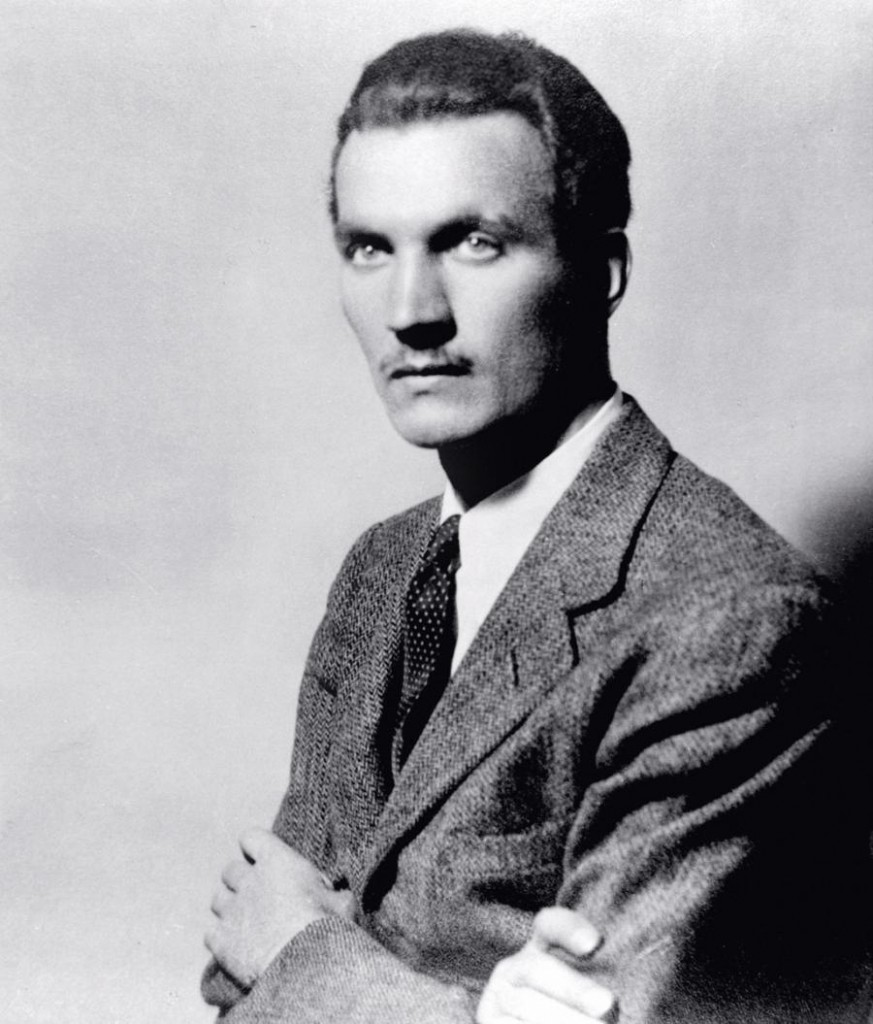

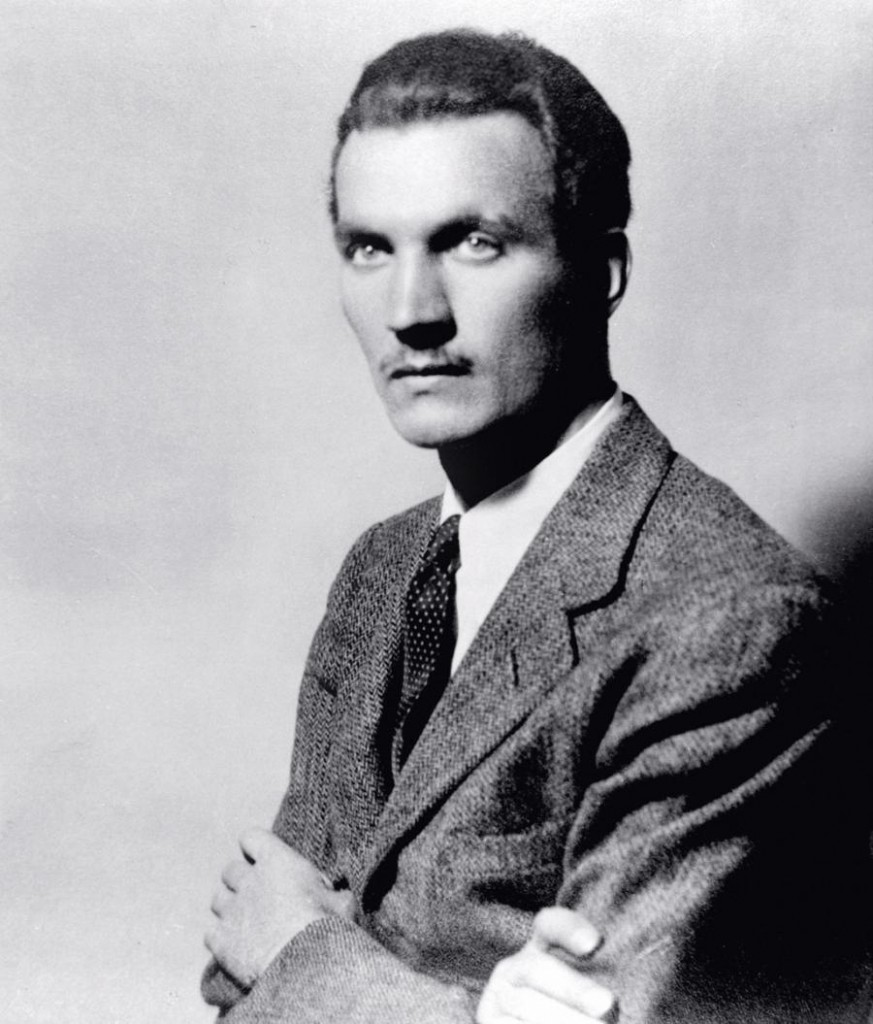

Jan Karski, Mission Accomplished” in Lublin, Poland. The two-day conference celebrated the centenary of the birth of

Jan Karski, a courier for the Polish Underground State who completed a number of precarious missions to inform the Allies about Nazi atrocities in Poland. Karski’s most important mission included several trips to the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp for Jews, where Karski witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust firsthand. Karski traveled to Great Britain using an elaborate ruse and false documents to pass through Germany, and ultimately reached the United States where he personally briefed President Roosevelt. Karski’s reports are considered to be the first, eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust to reach the West.

Despite Karski’s heroic efforts to inform the Allies about the plight of Poland and the Jews, he considered his mission to be a failure. The shocking information that he related to hundreds of officials and later thousands of members of the public, was often met with disbelief. Supreme Court Justice Felix Franfurter famously spoke of Karski after hearing his report, “

I did not say that he was lying, I said that I could not believe him. There is a difference.” Whether it was disbelief, indifference or cowardice, the Allies did not make rescuing Europe’s Jews a priority, and Adolf Hitler succeeded in killing most of them by 1945.

Karski was at a loss for what to do next at the end of the war. Poland, ostensibly the reason the world went to war in 1939, had now passed from Nazi to Communist domination. Karski would surely have been arrested by the NKVD had he returned to Poland, as were thousands of Home Army soldiers who were imprisoned or executed by the Soviet security apparatus.

Fortuitously, Karski was approached by Herbert Hoover, former President of the United States, and founder of the Hoover Institution on War Revolution and Peace (then known as the Hoover Library) at Stanford University in California. Hoover was impressed by Karski’s account of his experiences, popularized in the book

Story of a Secret State, and hired Karski to develop the Library’s Polish collections. Karski, whose family had received food relief after World War I, organized by the Herbert Hoover-led

American Relief Administration, was humbled and thrilled at the opportunity.

Karski was ultimately far more successful than anyone could have imagined. The most notable of his acquisitions was the negotiation of the transfer of the majority of the Polish Government in Exile’s records from London to Stanford, once the Allies had withdrawn recognition of that government, and recognized the Communist, puppet regime in Warsaw. Today the

Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest and largest source of Polish archival material outside of Poland. In the 1990’s the majority of Hoover’s Polish collections were microfilmed and transferred back to Poland, once she had regained her independence. The microfilms have since been digitized and are

available to anyone online. (For anyone interested in researching these online materials, feel free to contact me and I can help you navigate the somewhat confusing interface, nick@researchteacher.com) Karski also left his

personal papers to the Hoover Institution Archives. This collection includes his typed reports that were dictated from memory after his arrival in Great Britain and the United States, as well as a wealth of documentation relating to his post-war career.

Karski’s life after his year and a half stint as Hoover’s representative included a short-lived marriage and move to Venezuela and a much longer lasting stay at Georgetown University, where he received his PhD and taught international relations for many years. Karski kept the story of his wartime experiences to himself for decades, but was convinced to tell the story again, starting the 1970’s. He became a world-renowned figure for his efforts to bear witness for millions of persecuted Poles and Jews, who had few champions and fading hopes in those dark days in Eastern Europe.

Prior to giving my talk I was briefly interviewed by Polish Television in Lublin (TVP Lublin). I made it to the evening broadcast that was shown throughout the region.

Here is the link to an article, which contains the video in which I appear towards the end. I basically state that thanks to Jan Karski the Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest of their kind in the world.

Last week I attended the conference “Jan Karski, Mission Accomplished” in Lublin, Poland. The two-day conference celebrated the centenary of the birth of Jan Karski, a courier for the Polish Underground State who completed a number of precarious missions to inform the Allies about Nazi atrocities in Poland. Karski’s most important mission included several trips to the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp for Jews, where Karski witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust firsthand. Karski traveled to Great Britain using an elaborate ruse and false documents to pass through Germany, and ultimately reached the United States where he personally briefed President Roosevelt. Karski’s reports are considered to be the first, eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust to reach the West.

Despite Karski’s heroic efforts to inform the Allies about the plight of Poland and the Jews, he considered his mission to be a failure. The shocking information that he related to hundreds of officials and later thousands of members of the public, was often met with disbelief. Supreme Court Justice Felix Franfurter famously spoke of Karski after hearing his report, “I did not say that he was lying, I said that I could not believe him. There is a difference.” Whether it was disbelief, indifference or cowardice, the Allies did not make rescuing Europe’s Jews a priority, and Adolf Hitler succeeded in killing most of them by 1945.

Karski was at a loss for what to do next at the end of the war. Poland, ostensibly the reason the world went to war in 1939, had now passed from Nazi to Communist domination. Karski would surely have been arrested by the NKVD had he returned to Poland, as were thousands of Home Army soldiers who were imprisoned or executed by the Soviet security apparatus.

Fortuitously, Karski was approached by Herbert Hoover, former President of the United States, and founder of the Hoover Institution on War Revolution and Peace (then known as the Hoover Library) at Stanford University in California. Hoover was impressed by Karski’s account of his experiences, popularized in the book Story of a Secret State, and hired Karski to develop the Library’s Polish collections. Karski, whose family had received food relief after World War I, organized by the Herbert Hoover-led American Relief Administration, was humbled and thrilled at the opportunity.

Last week I attended the conference “Jan Karski, Mission Accomplished” in Lublin, Poland. The two-day conference celebrated the centenary of the birth of Jan Karski, a courier for the Polish Underground State who completed a number of precarious missions to inform the Allies about Nazi atrocities in Poland. Karski’s most important mission included several trips to the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp for Jews, where Karski witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust firsthand. Karski traveled to Great Britain using an elaborate ruse and false documents to pass through Germany, and ultimately reached the United States where he personally briefed President Roosevelt. Karski’s reports are considered to be the first, eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust to reach the West.

Despite Karski’s heroic efforts to inform the Allies about the plight of Poland and the Jews, he considered his mission to be a failure. The shocking information that he related to hundreds of officials and later thousands of members of the public, was often met with disbelief. Supreme Court Justice Felix Franfurter famously spoke of Karski after hearing his report, “I did not say that he was lying, I said that I could not believe him. There is a difference.” Whether it was disbelief, indifference or cowardice, the Allies did not make rescuing Europe’s Jews a priority, and Adolf Hitler succeeded in killing most of them by 1945.

Karski was at a loss for what to do next at the end of the war. Poland, ostensibly the reason the world went to war in 1939, had now passed from Nazi to Communist domination. Karski would surely have been arrested by the NKVD had he returned to Poland, as were thousands of Home Army soldiers who were imprisoned or executed by the Soviet security apparatus.

Fortuitously, Karski was approached by Herbert Hoover, former President of the United States, and founder of the Hoover Institution on War Revolution and Peace (then known as the Hoover Library) at Stanford University in California. Hoover was impressed by Karski’s account of his experiences, popularized in the book Story of a Secret State, and hired Karski to develop the Library’s Polish collections. Karski, whose family had received food relief after World War I, organized by the Herbert Hoover-led American Relief Administration, was humbled and thrilled at the opportunity.

Karski was ultimately far more successful than anyone could have imagined. The most notable of his acquisitions was the negotiation of the transfer of the majority of the Polish Government in Exile’s records from London to Stanford, once the Allies had withdrawn recognition of that government, and recognized the Communist, puppet regime in Warsaw. Today the Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest and largest source of Polish archival material outside of Poland. In the 1990’s the majority of Hoover’s Polish collections were microfilmed and transferred back to Poland, once she had regained her independence. The microfilms have since been digitized and are available to anyone online. (For anyone interested in researching these online materials, feel free to contact me and I can help you navigate the somewhat confusing interface, nick@researchteacher.com) Karski also left his personal papers to the Hoover Institution Archives. This collection includes his typed reports that were dictated from memory after his arrival in Great Britain and the United States, as well as a wealth of documentation relating to his post-war career.

Karski’s life after his year and a half stint as Hoover’s representative included a short-lived marriage and move to Venezuela and a much longer lasting stay at Georgetown University, where he received his PhD and taught international relations for many years. Karski kept the story of his wartime experiences to himself for decades, but was convinced to tell the story again, starting the 1970’s. He became a world-renowned figure for his efforts to bear witness for millions of persecuted Poles and Jews, who had few champions and fading hopes in those dark days in Eastern Europe.

Karski was ultimately far more successful than anyone could have imagined. The most notable of his acquisitions was the negotiation of the transfer of the majority of the Polish Government in Exile’s records from London to Stanford, once the Allies had withdrawn recognition of that government, and recognized the Communist, puppet regime in Warsaw. Today the Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest and largest source of Polish archival material outside of Poland. In the 1990’s the majority of Hoover’s Polish collections were microfilmed and transferred back to Poland, once she had regained her independence. The microfilms have since been digitized and are available to anyone online. (For anyone interested in researching these online materials, feel free to contact me and I can help you navigate the somewhat confusing interface, nick@researchteacher.com) Karski also left his personal papers to the Hoover Institution Archives. This collection includes his typed reports that were dictated from memory after his arrival in Great Britain and the United States, as well as a wealth of documentation relating to his post-war career.

Karski’s life after his year and a half stint as Hoover’s representative included a short-lived marriage and move to Venezuela and a much longer lasting stay at Georgetown University, where he received his PhD and taught international relations for many years. Karski kept the story of his wartime experiences to himself for decades, but was convinced to tell the story again, starting the 1970’s. He became a world-renowned figure for his efforts to bear witness for millions of persecuted Poles and Jews, who had few champions and fading hopes in those dark days in Eastern Europe.

Prior to giving my talk I was briefly interviewed by Polish Television in Lublin (TVP Lublin). I made it to the evening broadcast that was shown throughout the region. Here is the link to an article, which contains the video in which I appear towards the end. I basically state that thanks to Jan Karski the Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest of their kind in the world.

Prior to giving my talk I was briefly interviewed by Polish Television in Lublin (TVP Lublin). I made it to the evening broadcast that was shown throughout the region. Here is the link to an article, which contains the video in which I appear towards the end. I basically state that thanks to Jan Karski the Polish collections of the Hoover Library and Archives are the richest of their kind in the world.