Boris Nemtsov, one of the leaders of Russia’s democratic opposition movement, was shot four times in the back and killed while walking with his girlfriend on the

Moskvoretsky Bridge in Moscow on Friday, February 27, 2015. The only video camera that registered the shooting (that we know of) was far away from the attack.

This wasn’t a random killing or a crime of opportunity, this was a well-coordinated, political assassination. That no other cameras recorded the killing, which occurred several hundred meters from the Kremlin, presumably one of the most secure facilities on earth, raises many questions.

Did the assassins have the cooperation of someone who ordered the turning off of security cameras in the area? (Nearby cameras were

reportedly turned off for “maintenance” that day). Who benefits the most from Nemtsov’s murder? One of the first responses to emerge from the Kremlin about the murder was that it was certainly a “provocation”, as if to insinuate that Nemtsov may have been killed by members of the opposition to create a martyr out of him and embarrass Putin.

While the obvious motivation for the killing would be the removal of an opponent to Putin, as of two weeks ago, Nemtsov didn’t pose any obvious threat to Putin politically. The latest news is of the arrest of a number of Chechens as suspects in the slaying, suggested to have been motivated by Nemtsov’s support of the Charlie Hebdo journalists. This appears to be

far too convenient a story, which would both cast blame on a favorite target of the Russian government, the Chechens, while explaining the removal of a fierce critic of the regime.

Regardless of the specific motivations for the Nemtsov assassination, it is clear is that a strong and vocal anti-opposition movement has created a threatening and hostile environment against Russian supporters of democracy and human rights.

A key component of this phenomenon is the

Nashi youth movement, a government-backed organization that bills itself as democratic and anti-fascist, claims over 100,000 members and engages officially in political action in the form of rallies, marches, counter-protests, and unofficially in attacks and vandalism meant to intimidate the opposition.

I watched a

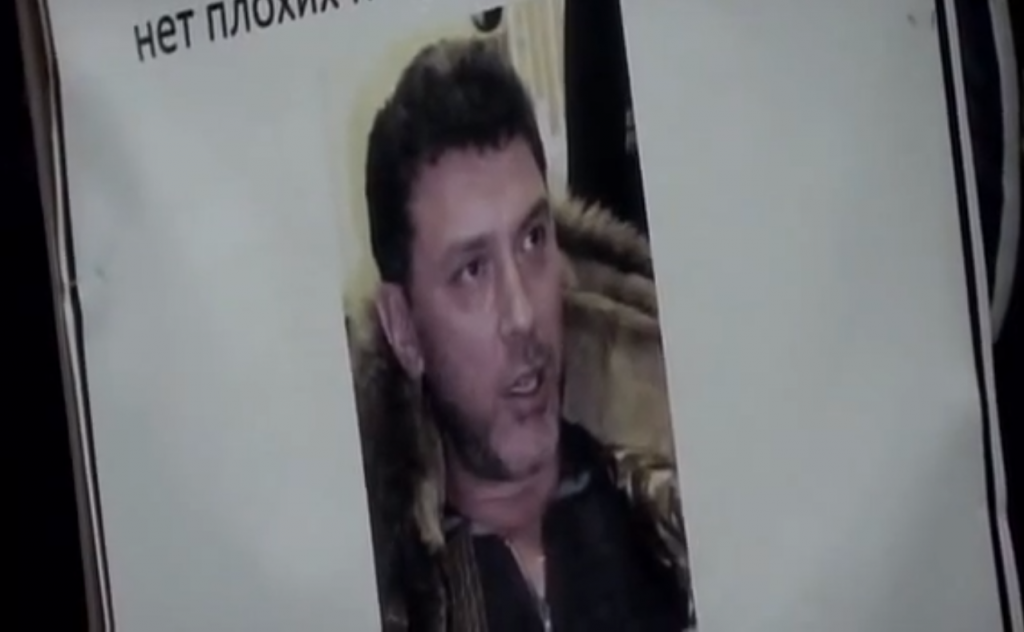

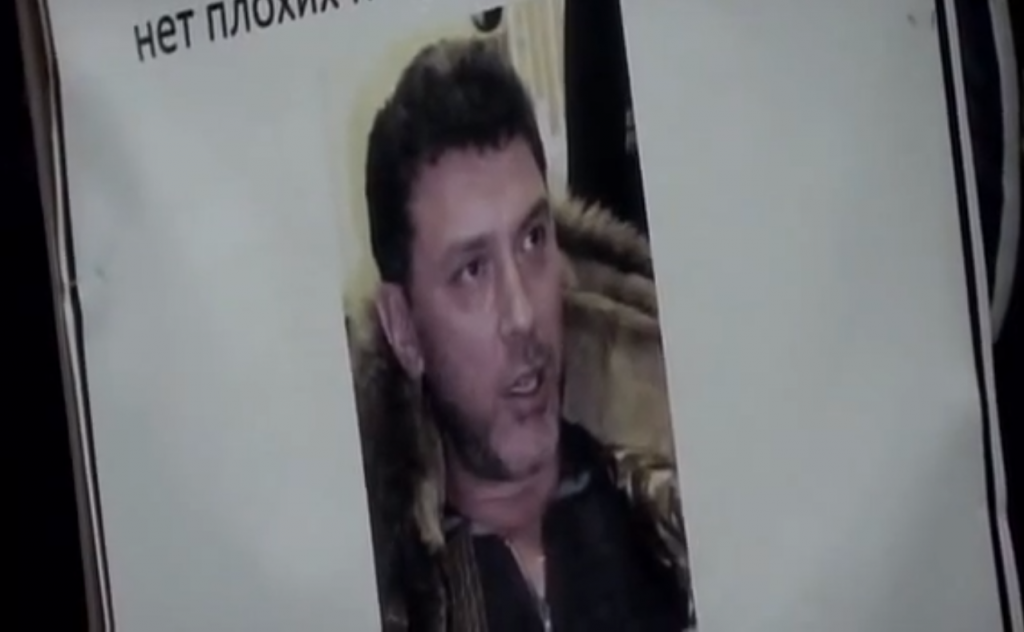

fascinating documentary about Nashi (translated from Russian to Polish), which included the very provocative scene of a ‘march of shame’, where dozens upon dozens of participants held signs with the pictures of ‘enemies’ who were “unworthy to live among us [Russians]”. Following chants of “shame, shame, shame” the signs were thrown down to the ground and then trampled upon. One of the signs bore the image of Boris Nemtsov:

The first thing that came to mind when I saw this was the image of Red Army soldiers casting Nazi German military banners onto the ground at Stalin’s feet during the

Moscow Victory Parade of 1945 in Red Square.

There is no evidence to suggest that the Nashi movement had any direct involvement in Nemtsov’s killing. What is clear though, is that these surrogates for the Russian government are intent on attacking the characters of those that criticize the regime and wish to see them gone from Russia.

In an

interview with Michał Kacewicz of Newsweek Poland, hours before he was shot, Nemtsov spoke about the dire situation in Russia. He described the present government as a type of hybrid fascist state that has convinced the majority of Russians (Putin has an 80% approval rating) through Goebbels-style propaganda, that the United States and the West are Russia’s great enemies and responsible for the

worsening economic situation.

While American and European leaders grapple with resolving Russia’s war in Ukraine, this larger issue is seemingly ignored, that being the near to mid-term political future of Russia itself. In his interview Nemtsov warned that time is rapidly slipping away to change the minds of Russians as to the devastating damage that Putin and his cohorts have done to the country.

The situation in Ukraine can be seen as a symptom of a resurgent Russian imperialism, backed by popular support and a deeply entrenched and well-funded security apparatus that will stop at nothing to prevent protests against the government similar to the Maidan in Ukriane. Only weeks ago the commemorations of the Maidan anniversary was countered by an

anti-Maidan protest in Moscow.

Boris Nemtsov died for his beliefs and his attempt to change Russia into a democratic and free country, where critics of the government need not live in fear for their lives. That vision of Russia appears to be a fading hope.

Boris Nemtsov, one of the leaders of Russia’s democratic opposition movement, was shot four times in the back and killed while walking with his girlfriend on the Moskvoretsky Bridge in Moscow on Friday, February 27, 2015. The only video camera that registered the shooting (that we know of) was far away from the attack.

This wasn’t a random killing or a crime of opportunity, this was a well-coordinated, political assassination. That no other cameras recorded the killing, which occurred several hundred meters from the Kremlin, presumably one of the most secure facilities on earth, raises many questions.

Did the assassins have the cooperation of someone who ordered the turning off of security cameras in the area? (Nearby cameras were reportedly turned off for “maintenance” that day). Who benefits the most from Nemtsov’s murder? One of the first responses to emerge from the Kremlin about the murder was that it was certainly a “provocation”, as if to insinuate that Nemtsov may have been killed by members of the opposition to create a martyr out of him and embarrass Putin.

While the obvious motivation for the killing would be the removal of an opponent to Putin, as of two weeks ago, Nemtsov didn’t pose any obvious threat to Putin politically. The latest news is of the arrest of a number of Chechens as suspects in the slaying, suggested to have been motivated by Nemtsov’s support of the Charlie Hebdo journalists. This appears to be far too convenient a story, which would both cast blame on a favorite target of the Russian government, the Chechens, while explaining the removal of a fierce critic of the regime.

Regardless of the specific motivations for the Nemtsov assassination, it is clear is that a strong and vocal anti-opposition movement has created a threatening and hostile environment against Russian supporters of democracy and human rights.

A key component of this phenomenon is the Nashi youth movement, a government-backed organization that bills itself as democratic and anti-fascist, claims over 100,000 members and engages officially in political action in the form of rallies, marches, counter-protests, and unofficially in attacks and vandalism meant to intimidate the opposition.

I watched a fascinating documentary about Nashi (translated from Russian to Polish), which included the very provocative scene of a ‘march of shame’, where dozens upon dozens of participants held signs with the pictures of ‘enemies’ who were “unworthy to live among us [Russians]”. Following chants of “shame, shame, shame” the signs were thrown down to the ground and then trampled upon. One of the signs bore the image of Boris Nemtsov:

Boris Nemtsov, one of the leaders of Russia’s democratic opposition movement, was shot four times in the back and killed while walking with his girlfriend on the Moskvoretsky Bridge in Moscow on Friday, February 27, 2015. The only video camera that registered the shooting (that we know of) was far away from the attack.

This wasn’t a random killing or a crime of opportunity, this was a well-coordinated, political assassination. That no other cameras recorded the killing, which occurred several hundred meters from the Kremlin, presumably one of the most secure facilities on earth, raises many questions.

Did the assassins have the cooperation of someone who ordered the turning off of security cameras in the area? (Nearby cameras were reportedly turned off for “maintenance” that day). Who benefits the most from Nemtsov’s murder? One of the first responses to emerge from the Kremlin about the murder was that it was certainly a “provocation”, as if to insinuate that Nemtsov may have been killed by members of the opposition to create a martyr out of him and embarrass Putin.

While the obvious motivation for the killing would be the removal of an opponent to Putin, as of two weeks ago, Nemtsov didn’t pose any obvious threat to Putin politically. The latest news is of the arrest of a number of Chechens as suspects in the slaying, suggested to have been motivated by Nemtsov’s support of the Charlie Hebdo journalists. This appears to be far too convenient a story, which would both cast blame on a favorite target of the Russian government, the Chechens, while explaining the removal of a fierce critic of the regime.

Regardless of the specific motivations for the Nemtsov assassination, it is clear is that a strong and vocal anti-opposition movement has created a threatening and hostile environment against Russian supporters of democracy and human rights.

A key component of this phenomenon is the Nashi youth movement, a government-backed organization that bills itself as democratic and anti-fascist, claims over 100,000 members and engages officially in political action in the form of rallies, marches, counter-protests, and unofficially in attacks and vandalism meant to intimidate the opposition.

I watched a fascinating documentary about Nashi (translated from Russian to Polish), which included the very provocative scene of a ‘march of shame’, where dozens upon dozens of participants held signs with the pictures of ‘enemies’ who were “unworthy to live among us [Russians]”. Following chants of “shame, shame, shame” the signs were thrown down to the ground and then trampled upon. One of the signs bore the image of Boris Nemtsov:

The first thing that came to mind when I saw this was the image of Red Army soldiers casting Nazi German military banners onto the ground at Stalin’s feet during the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945 in Red Square.

The first thing that came to mind when I saw this was the image of Red Army soldiers casting Nazi German military banners onto the ground at Stalin’s feet during the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945 in Red Square.

There is no evidence to suggest that the Nashi movement had any direct involvement in Nemtsov’s killing. What is clear though, is that these surrogates for the Russian government are intent on attacking the characters of those that criticize the regime and wish to see them gone from Russia.

In an interview with Michał Kacewicz of Newsweek Poland, hours before he was shot, Nemtsov spoke about the dire situation in Russia. He described the present government as a type of hybrid fascist state that has convinced the majority of Russians (Putin has an 80% approval rating) through Goebbels-style propaganda, that the United States and the West are Russia’s great enemies and responsible for the worsening economic situation.

While American and European leaders grapple with resolving Russia’s war in Ukraine, this larger issue is seemingly ignored, that being the near to mid-term political future of Russia itself. In his interview Nemtsov warned that time is rapidly slipping away to change the minds of Russians as to the devastating damage that Putin and his cohorts have done to the country.

The situation in Ukraine can be seen as a symptom of a resurgent Russian imperialism, backed by popular support and a deeply entrenched and well-funded security apparatus that will stop at nothing to prevent protests against the government similar to the Maidan in Ukriane. Only weeks ago the commemorations of the Maidan anniversary was countered by an anti-Maidan protest in Moscow.

Boris Nemtsov died for his beliefs and his attempt to change Russia into a democratic and free country, where critics of the government need not live in fear for their lives. That vision of Russia appears to be a fading hope.

There is no evidence to suggest that the Nashi movement had any direct involvement in Nemtsov’s killing. What is clear though, is that these surrogates for the Russian government are intent on attacking the characters of those that criticize the regime and wish to see them gone from Russia.

In an interview with Michał Kacewicz of Newsweek Poland, hours before he was shot, Nemtsov spoke about the dire situation in Russia. He described the present government as a type of hybrid fascist state that has convinced the majority of Russians (Putin has an 80% approval rating) through Goebbels-style propaganda, that the United States and the West are Russia’s great enemies and responsible for the worsening economic situation.

While American and European leaders grapple with resolving Russia’s war in Ukraine, this larger issue is seemingly ignored, that being the near to mid-term political future of Russia itself. In his interview Nemtsov warned that time is rapidly slipping away to change the minds of Russians as to the devastating damage that Putin and his cohorts have done to the country.

The situation in Ukraine can be seen as a symptom of a resurgent Russian imperialism, backed by popular support and a deeply entrenched and well-funded security apparatus that will stop at nothing to prevent protests against the government similar to the Maidan in Ukriane. Only weeks ago the commemorations of the Maidan anniversary was countered by an anti-Maidan protest in Moscow.

Boris Nemtsov died for his beliefs and his attempt to change Russia into a democratic and free country, where critics of the government need not live in fear for their lives. That vision of Russia appears to be a fading hope.

One thought on “Boris Nemtsov’s Murder in the Shadow of the Kremlin”